I don’t remember how old I was when my brother told me our grandfather had passed away. I could look it up, I have the paperwork in a lockbox in a room downstairs. There’s all kinds of paperwork in there. Birth certificates, marriage licenses, and death certificates. The cliff notes version of the story of a life. The days that were important enough that they needed witnesses. What isn’t in that box are the moments in between all those official dates when someone wasn’t there to confirm the events. Those are what actually tell the sometimes grand and sometimes small tales of our time here on earth.

For no real reason at all, I think it was a Sunday morning. I was lying in my bed at the time, the top portion of the bunk beds I had at one time shared with my brother, but no longer did. There was a stereo on top of a dresser by the bed that I could reach from the bunk. I usually slept with a CD on repeat because I have always hated trying to sleep at the mercy of my own thoughts, and preferred a soundtrack. Since I didn’t have to share the room with anyone, I could put the music on repeat, and it would play the whole night without bothering anyone else.

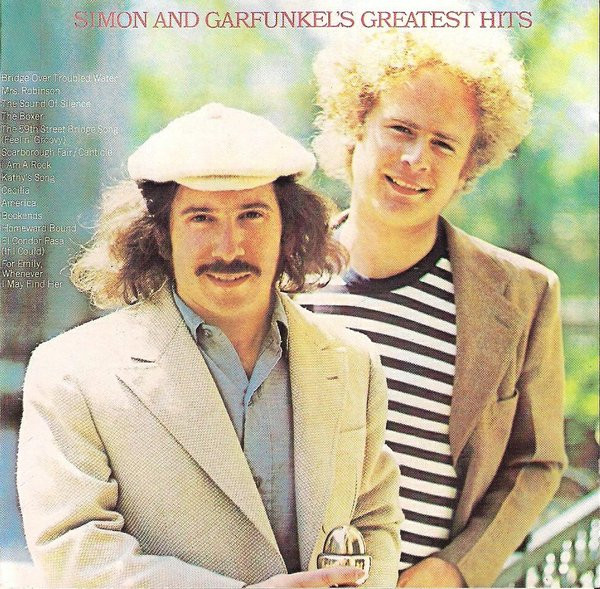

That night, it was Simon and Garfunkel’s greatest hits, from 1972 where they look so happy on the cover. Paul Simon with a righteous mustache and unruly hair spilling every direction from under his hat, and Art Garfunkel behind him with his blond afro disappearing into the sunshine. The one with the live version of “Homeward Bound” that I somehow never copped to it being live until a few years ago, when I decided to listen to all their albums for the first time and marveled at the big, full drums on the studio version. They’re not there at all on the Carnegie Hall recording on the greatest hits album. I’m still a little gobsmacked at how different the two versions are. The same with the “59th Street Bridge Song”, except that I really dislike the studio version of that one.

The song that would have been playing when my brother came in was “For Emily, Wherever I May Find Her”, which was another live track. This one from St Louis. It’s the second song on the CD. The funny thing is, despite the dramatic crescendo of that song, I have no recollection of it at that moment at all. What I truly remember, in my bones, is as my brother left the room, and The Boxer coming on.

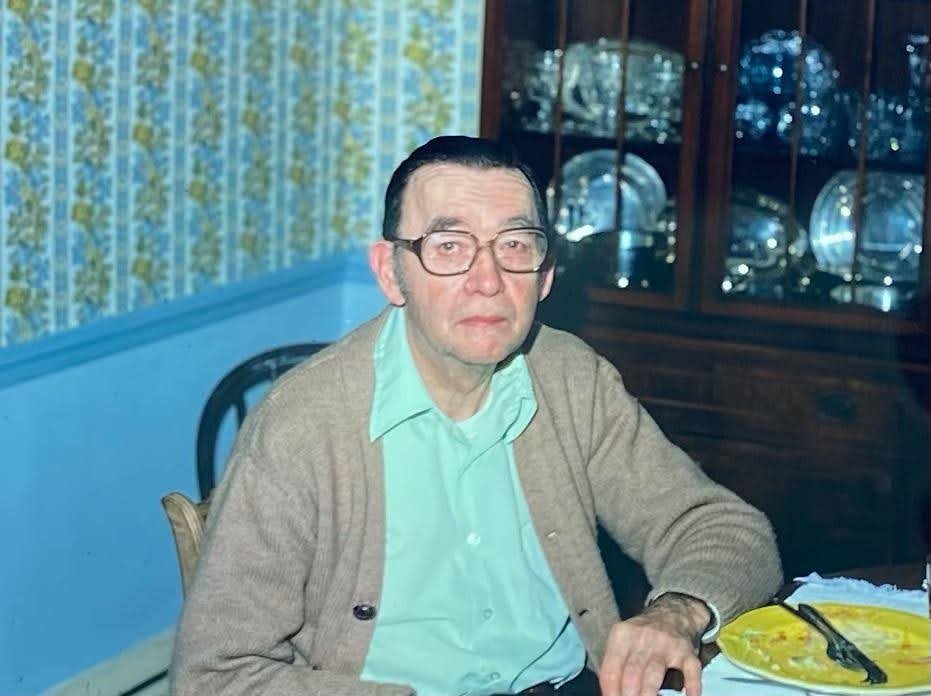

My grandfather on my mother’s side, Harold, was the first of my close family to pass away. My father’s mother, my grandmother, had died when he was young, and as such, I never knew her beyond a few stories and a picture of her with my dad when he was small.

To speak truly, I did not know my grandfather well. He had had a stroke some years prior that had badly damaged his vocal chords, and I had trouble understanding him. I can still remember the sound of his voice, but no words that he said. From everything I have been told about him since, I wish my younger self was just a bit more willing to try and hear and understand.

The storybook finger picking that begins the Boxer before the guitar resolves into the bouncing rhythm that drives the song will forever take me back to that moment. I vividly recall rolling onto my back, looking up at the posters taped to my ceiling, and wondering if tears would come.

The Boxer tells the story of a man who arrives in New York City and finds only the cold, harsh life of the poor and downtrodden. There are plenty of interpretations of Paul Simon’s lyrics, some saying the song is an attack on Bob Dylan and his self-mythologizing, leading to the ‘Lie lie lie’ chorus, others from Simon himself saying it is largely autobiographical. Whatever the true meaning, for me, in that moment, trying to understand my own feelings, it became the story of my grandfather.

He wasn’t a boxer, to be certain, he was a minister in the Methodist church, as was his father and his daughter. He wasn’t a large man, and certainly not imposing like a boxer might be. Despite my inability to understand his voice, his gentleness and kindness was always apparent. You don’t need working vocal chords for those traits to be understood. More than all of that, he was a conscientious objector, refusing to pick up a gun and go to war. He had as much fight in him as any man who ever threw a punch, but he directed it towards peace and compassion.

I think that is why the song became so fixed for me in that moment. It’s the last verse,

In the clearing stands a boxer

And a fighter by his trade

And he carries the reminders

Of every glove that laid him down

Or cut him till he cried out

In his anger and his shame

“I am leaving, I am leaving”

But the fighter still remains

Those words speak to the kind of strength my grandfather had. He had left that day, but ‘The fighter still remained’.

I didn’t cry. Not until later, when my mother spoke at his memorial service. She got choked up while speaking about her now departed father. It was the first time I remember seeing my mother cry. I don’t think I fully understood the loss until then. Maybe I still don’t.

My mother is the last remaining of her nuclear family, and there aren’t many left beyond her who truly knew my grandfather. What I know, as I mentioned, is through stories told long after his passing at family gatherings. His story will someday, far too soon, be shrunk down to those dates on papers in a metal box, a story “seldom told.” It feels sadder now than it did then.

I don’t have a neat way to wrap this up. I had sat down at my computer to do some work, and when the song came on, it derailed me completely. Writing is a funny compulsion that way. Just something in the air tonight, I guess. This isn’t much more than a remembrance of my grandfather and a song that is tied to him.

Maybe what I said up top about moments not having witnesses wasn’t true, or at least not all the way true. In that moment of my learning, and of death coming a little bit closer, Paul Simon, Art Garfunkel, and the unnamed boxer were there to witness my moving from one stage of life to another. Maybe that’s enough.

Leave a comment